Why in the News?

Recently, a 7-Judge Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court, in State of Punjab & Others v Davinder Singh & Others case, held that sub-classification of Scheduled Castes (SCs) is permissible to grant separate quotas for more backwards within the SC categories.

More on the News

- 7-judge Constitution Bench was essentially considering two aspects:

- whether sub-classification within reserved castes be allowed, and

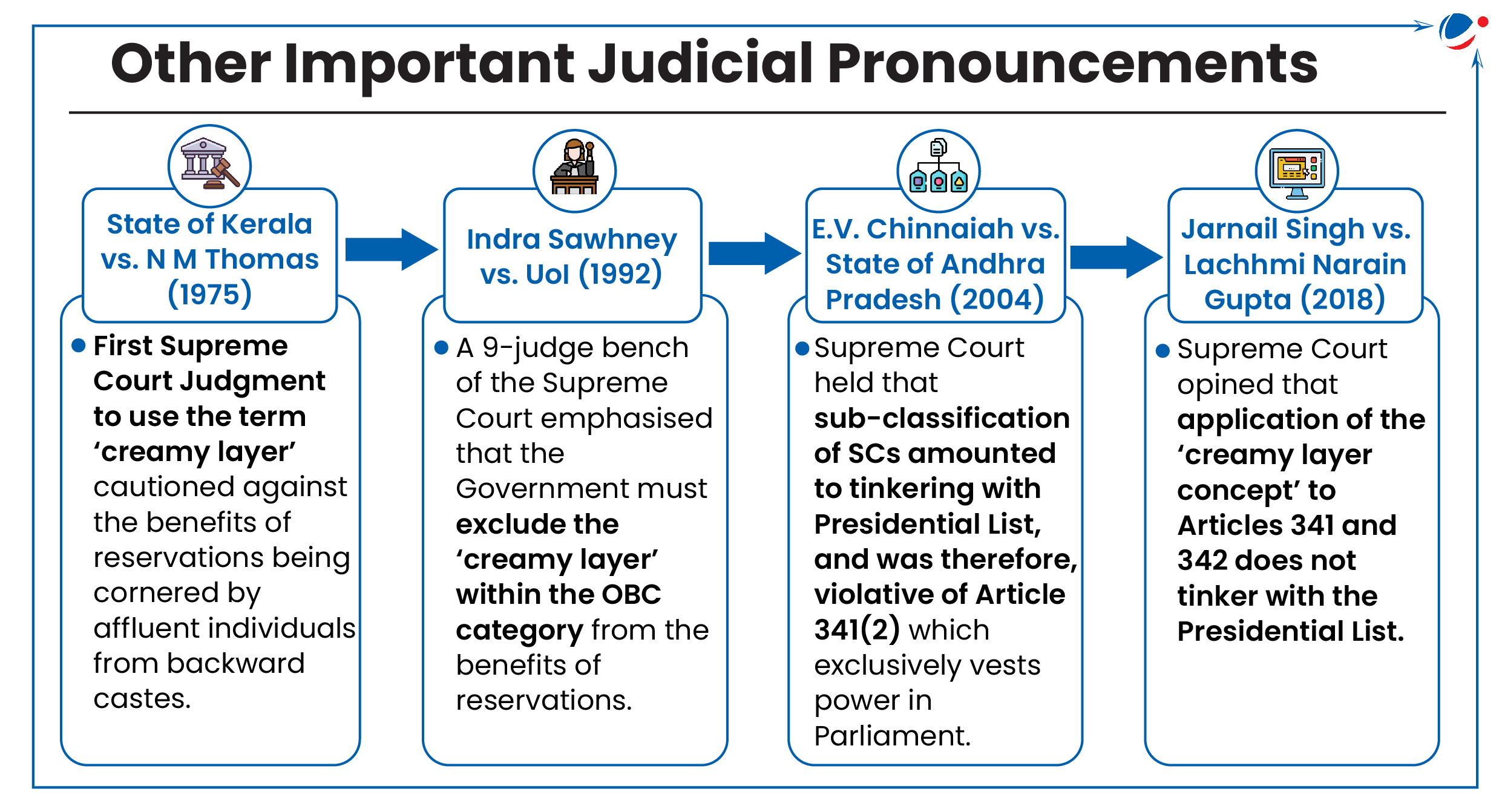

- correctness of the decision in E. V. Chinnaiah v. State of Andhra Pradesh (2005), which held that SCs notified under Article 341 formed one homogenous group and could not be sub-categorized further.

- Previously, in 2014, the Supreme Court in Davinder Singh v. State of Punjab referred the appeal to reconsider the judgment in E.V. Chinnaiah Case (2004) to a 5-judge Constitution Bench.

- In 2020, a 5-Judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court ruled that the E.V. Chinnaiah judgement, which prohibited sub-categorization of SCs, requires reconsideration.

Key highlights of the Judgment

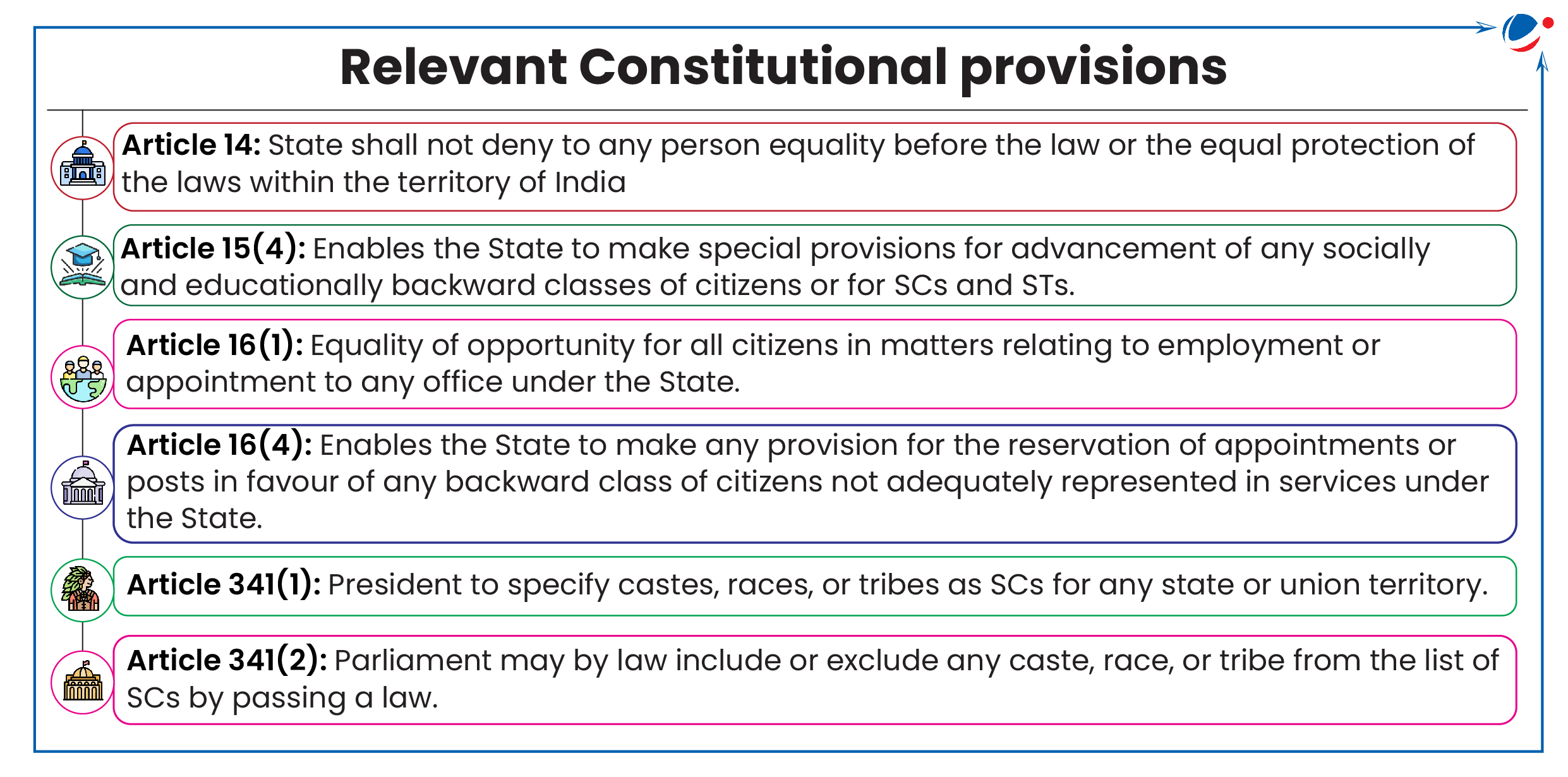

- Sub-classification within the SCs does not violate Article 341(2) because the castes are not per se included in or excluded from the List.

- Scope of sub-classification of SCs:

- Objective of any form of affirmative action including sub-classification is to provide substantive equality of opportunity for the backward classes.

- Substantive equality refers to the principle that the law must account for the different backgrounds and historical injustices faced by persons or groups.

- State can sub-classify based on inadequate representation of certain castes. However, the State must establish that the inadequacy of representation of a caste/group is because of its backwardness.

- State must collect data on the inadequacy of representation in the "services of the State".

- Objective of any form of affirmative action including sub-classification is to provide substantive equality of opportunity for the backward classes.

- State cannot act on its whims or political expediency and its decision is amenable to judicial review.

- State is not entitled to reserve 100% of the seats available for SCs in favour of a group to the exclusion of other castes in the President's List.

- SCs notified under Article 341(1) of the Constitution are heterogeneous groups of castes, races or tribes with varying degrees of backwardness.

- Four of the seven judges on the Bench separately opined that the government should extend the "creamy layer principle" to SCs and STs.

- However, the opinions do not constitute a direction to the government to implement the creamy layer concept, as the issue did not directly arise in this case.

Arguments for sub-classification | Arguments against sub-classification |

|---|---|

|

|

Conclusion

In the wake of the recent Supreme Court judgment, it is crucial for policymakers to engage in comprehensive dialogue with all stakeholders, including SC community representatives, legal experts, and social scientists. In this regard, Government may constitute a commission on the lines of G. Rohini Commission (constituted for sub-categorization OBCs) with an aim to find a solution that addresses disparities within the SC category while preserving the unity and collective progress of the community as a whole.