Why in the News?

Union Home Minister introduced the Constitution (One Hundred and Thirtieth Amendment) Bill, 2025 in the Lok Sabha.

More on the News:

- Bill seeks to provide for removal of the Prime Minister, Chief Minister or any other Minister in central and state governments, and the Union Territory (UT) of Delhi who is held in custody for 30 consecutive days for a serious criminal offense.

- The Bills propose significant amendments to Articles 75, 164, and 239AA of the Indian Constitution.

- The same provisions are extended to UT of Puducherry through the Government of Union Territories (Amendment) Bill, 2025 empowering the president to act similarly.

- The Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization (Amendment) Bill, 2025 also applies the same provisions to Jammu & Kashmir, allowing the LG to remove the CM/Ministers.

- All three bills have been referred to the Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) for detailed examination and discussion.

Key provisions of Constitution Amendment Bill, 2025:

- Grounds for Removal: A Union Minister, Chief Minister (CM), or State Minister will be removed from office if they are arrested and detained in custody for 30 consecutive days for an offense punishable with five or more years of imprisonment.

- This also applies to the Prime Minister.

- Procedure for Removal:

- For Union Ministers (excluding PM): The President must remove the Minister on the Prime Minister's advice, to be tendered by the 31st day of detention. If no advice is given, the Minister will automatically cease to hold office from the 31st day.

- For State Ministers (excluding CM): A similar provision applies, with the Governor acting on the advice of the Chief Minister. If the CM does not advise by the 31st day, the Minister automatically loses office.

- For Delhi Ministers (excluding CM): The President removes the Minister on the advice of Delhi's Chief Minister. If no advice is tendered, the Minister automatically ceases to hold office.

- For Prime Minister or Chief Ministers (Union/State/Delhi): The Prime Minister or Chief Minister must tender their resignation by the 31st consecutive day of custody. If they fail to resign, they will automatically cease to hold office from the day thereafter.

- No bar on Reappointment: Reappointment of a Minister, Prime Minister, or Chief Minister is allowed after their release from custody.

Arguments in favor of Bills:

- Constitutional Morality and Ethical Governance: SC in Manoj Narula v. Union of India (2014) had indicated that morality is intrinsic to constitutional framework, urging against appointing persons with serious criminal charges as Ministers.

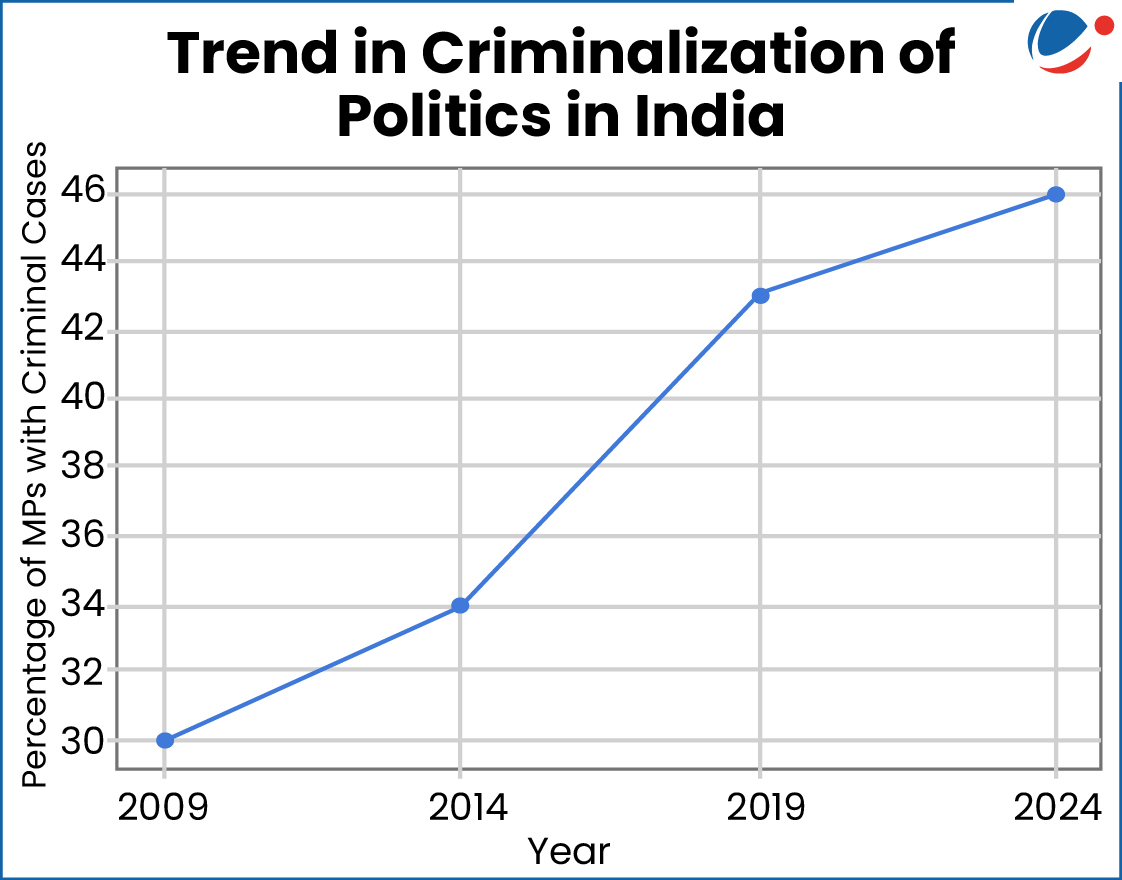

- Protecting Public Trust: This measure is seen as a strong stance against corruption and the criminalization of politics, potentially enhancing public trust in institutions.

- Good Governance: It seeks to eliminate anomaly of "governance from jail," aligning executive functions with accountability and addressing constitutional gaps in accountability.

- Bridging Legal Gap: The existing Representation of People Act (RP Act) disqualifies elected representatives only after conviction. This Bill addresses the interim period of arrest and detention, bridging a crucial legal gap.

- Fairness with Other Employees: Ordinary government employees face suspension after 48 hours in custody; similar standards should apply to Ministers.

- Other: Uniform party application, advances political decriminalization, Balancing Frivolous Arrests and Judicial Scrutiny etc.

Arguments against the Bills:

- Political Weaponization and Threat to Federalism: Central agencies like the ED and CBI could be misused to arrest leaders on flimsy charges, providing a "legal shortcut" to destabilize governments without electoral contest.

- Presumption of Innocence at Stake: The Bill is against the principle of "innocent until proven guilty" and natural justice by triggering removal based on detention alone, without conviction or even the framing of charges.

- The SC in Lily Thomas v. Union of India held that disqualification begins only upon conviction, not arrest or detention.

- Inconsistency in Treatment: There is an inconsistency between legislators and Ministers.

- While Members of Parliament (MPs) and State Legislatures (MLAs) are disqualified only upon conviction under the RP Act, 1951 Ministers under this Bill could be forced to resign on mere detention.

- This creates a paradox where a convicted legislator might continue as a Minister longer than an arrested Minister.

- "Revolving Door" Problem: The provision allowing reappointment after release from custody could lead to cycles of resignation and reinstatement, causing political instability and potentially incentivizing tactical legal maneuvers.

- Executive Discretion and Politicization: The dual mechanism of removal (PM/CM's advice or automatic cessation) could politicize the process, allowing a Prime Minister to protect allies or remove a hostile Chief Minister to target rivals.

- Lack of Safeguards: No provision for compensation if the arrest is found to be malicious.

- It can encourage misuse of preventive detention and laws like Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967 (UAPA) and Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA).

- E.g. of the 5,000 cases registered by ED in past five years, there were less than 10% convictions.

- It can encourage misuse of preventive detention and laws like Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967 (UAPA) and Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA).

Existing legal framework and Judgments for disqualification after crimes

|

Way Forward:

- Interim Suspension: Rather than outright removal, law could provide for interim suspension of ministerial functions during ongoing trials, allowing governance to continue without compromising accountability.

- Strengthening Political Parties' Role: Political parties must instill self-discipline and commit to not fielding candidates with criminal records, focusing on integrity rather than mere "winnability".

- Law Commission Recommendations: Recommended that the framing of a charge for offences punishable by up to five years' imprisonment should be made an additional ground for disqualification.

- This would filter out frivolous or politically motivated arrests by ensuring initial judicial scrutiny.

- Making Bail a Rule: It is suggested to make bail a rule except in heinous violent crimes so that new provisions regarding removal have wider acceptability.

- Fast-tracking Criminal Cases: Instead of disqualifying Ministers merely based on arrest, the focus should shift to fast-tracking serious criminal cases against Ministers, ensuring impartial investigations and swifter trials.

- Establishing an Independent Review Mechanism: Like a tribunal or a judicial panel, could examine whether conditions for removal have been met, preventing executive overreach and ensuring impartial application.